Editor’s note: This piece by Donald Bryson was published first at RealClearHistory.

Victory over Japan Day reminds us what American exceptionalism is made of

Published September 8, 2022

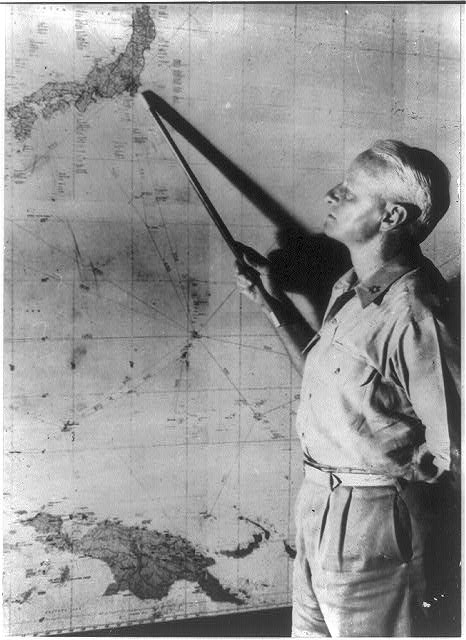

September 2, 1945, and its display of American military strength was, in many ways, the culmination of Japanese Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto’s famous quote after the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941: “I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.”

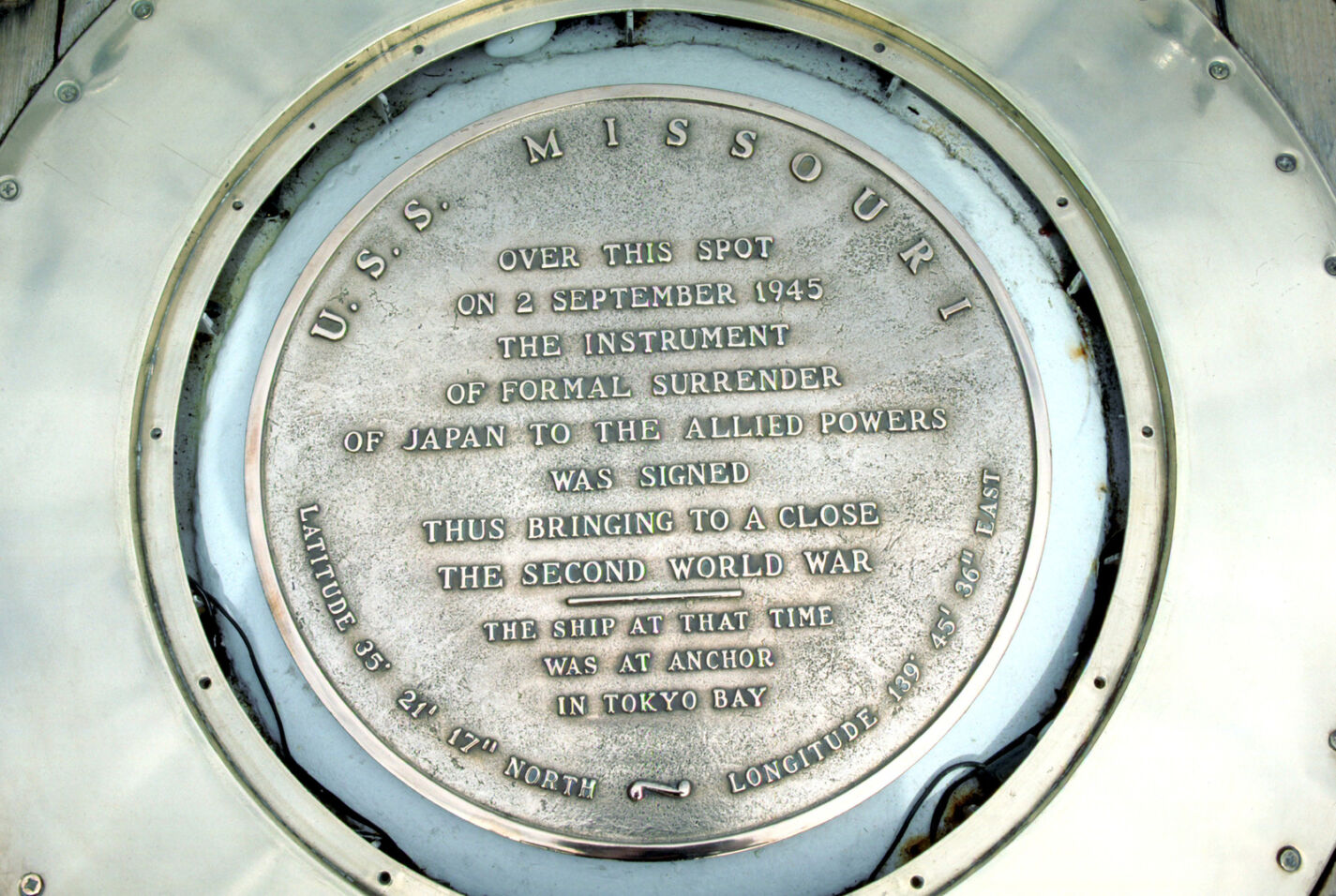

Most years, September 2 passes with few Americans giving it much thought. However, this historic date is worthy of our reflection, if for no other reason than it marks the end of the most terrible conflict in history – the Second World War. And so today, we celebrate the victory of free people over despotic aggressors, specifically the United States’ victory over Japan.

Although some nations designate Victory Over Japan (VJ) Day on other dates, the United States commemorates September 2 because it was the day the leaders of Japan signed the Instrument of Surrender. Shortly after 9 AM on September 2, 1945, on the deck of the USS Missouri (BB-63) in Tokyo Bay, New Zealand’s Air Vice-Marshal Leonard Isitt added his signature to the Instrument of Surrender between the Allied powers and Japan. Isitt was the twelfth and final signatory, and the Second World War concluded with his signature.

A few moments after Isitt’s signature, 349 American carrier airplanes – a mix of Grumman F6F Hellcat fighters, Curtiss SB2C Helldiver dive bombers, and other aircraft – flew in massed formation overhead in a purposefully overwhelming display of American military power. They were followed by 462 Boeing B-29 Superfortress heavy bombers, flying over the nearly 200 Allied vessels in Tokyo Bay.

While the conclusion of this global conflict was a seminal point in world history, this moment was more than the end of a war. It sealed the United States as a global military hegemon after overwhelming displays of land-based power in Europe and naval power in the Pacific. The land-based capabilities of the United States Army were logistically superior, but not numerically or technologically, to other nations at the end of the Second World War; however, it was the ascendance of the United States Navy that allowed America to project hard power in multiple directions almost infinitely.

As Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz put it after the war, “It is the function of the Navy to carry the war to the enemy so that it is not fought on U.S. soil.”

Admiral Yamamoto’s “sleeping giant” quote was not about American service members, differences in races, or a fear of some innate bravery in Americans. It was a fear of Army divisions and naval fleets of American citizens with political agency in a democratic system of government, operating within a capitalist economy fueled by massive natural resources unknown to Japan. Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in late 1941 did not cause the American people to whither; instead, it formed a fighting spirit and purpose which proved insurmountable to the forces of racist, fascist governments in Europe and Asia.

The ascendance of the American Navy came not because Americans were uniquely better sailors but because the American economy had the vast capacity to deliver fuel, increasingly higher-quality weaponry, and personnel across 6,000 miles of ocean at a feverish rate.

Why? Because industrialists and the workers of America were not compelled into action, the federal government did not take over the means of production and research. Instead, businesses freely entered into contracts with the government for mass production and arms research.

Communism holds that the nation-state or government should own and control the means of production – the Soviet Union represented this. Fascism, represented by Germany, Italy and Japan, supported a blend of public and private ownership of production, but always with central government planning dictating the means and product.

Capitalist economies, like those of the United States and United Kingdom, supported complete private ownership of production, with price and product need being determined by the customer, which in the case of wartime happened to be the government.

The result was the most effective and far-reaching war economy ever seen. It was as if the American economy had declared war.

Aircraft production took off exponentially in terms of quantity and quality. At the time of Pearl Harbor and Midway, American aircraft were generally inferior to those of the Japanese. But by 1943, the Grumman Corporation was producing the F6F Hellcat fighter in Hicksville, New York. More than 12,000 of these planes were made in two years. The Hellcat’s remarkable 19:1 kill ratio is only surpassed by the fact that the Hellcat went from the experimental stage to production in only 18 months.

The Curtiss SB2C Helldivers, which flew along with the Hellcats over the USS Missouri on VJ Day, were produced at a plant in St. Louis, MO. The Boeing B-29 Superfortresses, which followed the carrier planes over Tokyo Bay, were built at plants in Georgia, Kansas, and Washington.

Naval production also ramped up at a pace that dwarfed the Japanese shipbuilding industry. In his 2001 book “Carnage and Culture,” historian Victor Davis Hanson found, “During the four years of the war the Americans constructed sixteen major warships for every one the Japanese built.”

The Essex-class aircraft carrier USS Yorktown (CV-10) served throughout the Pacific War and was built in Newport News, VA. The Iowa-class battleship on which the Japanese military surrendered, the USS Missouri, was built in Brooklyn, NY.

Another example of the vastness of the American war machine is more personal for me. More than 1,400 miles south of Tokyo on that fateful September 2, my great-grandfather, nineteen-year-old Seaman First Class Preston Nowell, was aboard the USS Trousdale (AKA-79) – a Tolland-class attack cargo ship built by the North Carolina Shipbuilding Co. in Wilmington, North Carolina, in 1944. The Trousdale was anchored in Saipan and was just a couple of months removed from receiving its lone battle star of the war at Okinawa.

Why was the Trousdale in Saipan instead of in Tokyo Bay? Because it had just offloaded supplies in Tinian, the American airbase for most B-29 bombers in the Pacific, in preparation for the coming land invasion of Japan’s Home Islands.

All of America, not just the politicians, sailors, and soldiers, went to war in the early 1940s. The effects were a total war against her enemies, leading to surrender documents that shaped the rest of the century.

Like thousands of other Navy veterans, my grandfather received a letter from Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal in 1946. While it was a simple form letter, it is remarkable for its brevity and honesty in what had been accomplished by the Navy.

“You have served in the greatest Navy in the World,” Forrestal wrote. “It crushed two enemy fleets at once, receiving their surrenders only four months apart. It brought our land-based airpower within bombing range of the enemy, and set our grand armies on the beachheads for final victory.”

Forrestal continued, “No other Navy at any time has done so much.”

It is easy in the current political climate to grow soft on the idea of American exceptionalism. The idea that America is exceptional because it was built upon republican ideals, such as free enterprise, civic engagement, and the rule of law, can seem quaint. But we should never forget that it was for those ideals that America was exceptional and may continue to be so.

For the sake of our future and our children, I firmly hope that we never forget the ideals that let young men like my great-grandfather save the world once. This year, Victory Over Japan Day should serve as a reminder that the Greatest Generation’s birthright is also available to us and any who choose to call this unparalleled republic home.

Donald Bryson is President of the John Locke Foundation, a free-market think tank based in Raleigh, North Carolina.