"Late" Absentee by Mail Voters: Who Are They?

Published June 17, 2021

With the passage in the state senate of Bill 326, the move to require absentee by mail ballots by received by Election Day, instead of three days afterwards, has cleared half a legislative hurdle. This legislation was brought about due to the controversy over the extension in 2020's election of receiving absentee by mail ballots from three days after the election to nine days.

But how big an issue are mail-in ballots arriving after Election Day in North Carolina? Luckily, the N.C. State Board of Elections' public data allows us to see how many mail-in ballots were received and accepted after election day and what kind of partisan (and other) dynamics, if any, are at work.

First, the numbers of how many absentee by mail (ABM) ballots come in after Election Days since the 2014 general election. In 2014's midterm election, over 76,000 ABM ballots were accepted, with nearly 4,700 coming in and being accepted after Nov. 4, amounting to six percent of the total ABMs cast.

In 2016's presidential election, more than double the 2014 ABM ballots were returned and accepted, yet the percentage of 'late arrivals' was roughly the same: five percent, or nearly 10,000 came in and were accepted after Nov. 8th that year.

In 2018's midterm, almost 100,000 ABMs were returned and accepted, but a larger percentage of them came after November 6: 11,501 were returned and accepted after Election Day, amounting to 12 percent of the total.

Finally, the 2020 election, operating under a global pandemic, broke the record for the use of absentee by mail ballots in North Carolina, with nearly one million ABMs coming in and being accepted. But of that total, nearly 13,500--or one percent--of those ballots came after November 3's election day, slightly ahead of the same numbers in 2016 and 2018.

Of course, we don't know how these 'after Election Day' ballots broke in terms of votes for candidates, but based on the data provided by the NCSBE, we do know from whom these ballots came from.

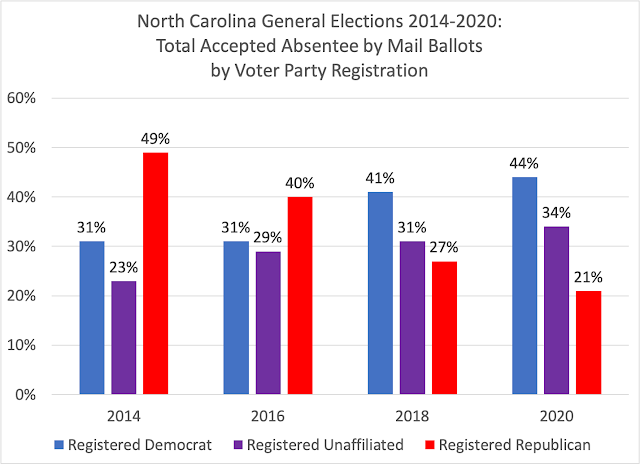

First, the party registrations of voters show distinct differences between the overall ABMs totals and the 'late voter' pool of ABM ballots. To give a comparative sense, this chart shows the party registration percentages of for all returned and accepted ABMs for each of the four elections.

In 2014 and 2016, registered Republicans dominated the absentee by mail vote method, with nearly half of the ABMs in 2014 and 40 percent in 2016. In 2018 and 2020, however, registered Democrats took the lead, with slight increases in registered unaffiliated voters in comparison to the previous two elections. In 2018, a perceived Democratic wave year, and in 2020, the distinctive difference between Democrats utilizing mail-in voting and Republicans choosing to vote in-person, likely speaks to the differences among these elections.

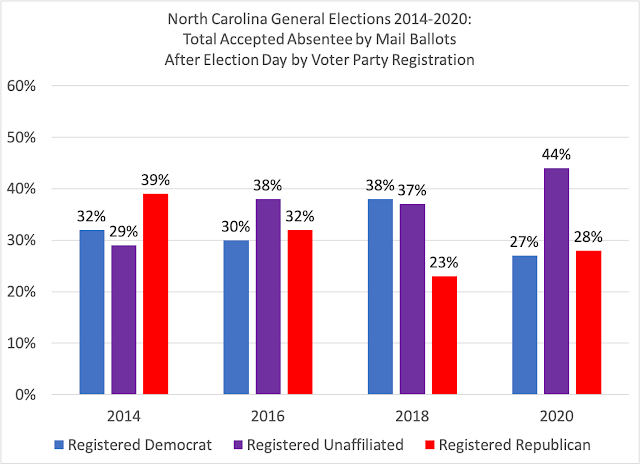

Among the 'late arriving' ABMs, however, there are notable shifts when it comes to party dynamics, as noted in this next chart.

In 2014's election, the late arrivals (those returned after Election Day and accepted) mirrored the overall general pool of mail-in ballots, but had a slightly higher level of unaffiliated voters present. In 2016 and afterwards, the differences of late arriving ABMs is notably for the increase in the unaffiliated voter as a disproportionate share of the pool. Note the 2020 numbers, where nearly 45 percent of the late arriving ABMs came from registered unaffiliated voters, while basically both party registrants were tied.

This increase in the presence of unaffiliated voters could be due to these voters being 'late deciders' in the election, thus holding their mail-in ballots to the last possible moment before making their decisions.

In looking at the racial dynamics of late arriving mail-in ballots, the percentage of white voters casting late ballots tends to match the overall pool of absentee by mail voters. In 2020, 62 percent of late-arriving ballots were from white voters, compared to 69 percent in the overall absentee by mail pool. The biggest jump in late arriving mail-in ballots compared to their overall ABM percentage was among voters who we don't know their race: voters with an "unknown" or unreported racial classification went from 10 percent of the total ABM pool to nearly 20 percent of the late arrivals.

While there is still question on whether SB 326 will become law (the greatest hurdle will likely be a gubernatorial veto), the overall dynamics of late arriving ballots via the mail in North Carolina is important to note, even though the numbers may seem minuscule. For example, the late arriving AMB ballot percentage of all ballots cast (absentee by mail, absentee one-stop, and Election Day votes) in each of the past four elections amounted to between two-tenths of one percent in 2014, 2016, and 2020 to three-tenths of one percent in 2018.

Of course, with the potential closeness of elections in this state (witness the 400-vote difference in the 2020 chief justice election), the differences of five to fifteen thousand votes could be a deciding factor in future elections.

One other argument has been made for the "Election Day Integrity Act's" passage. For those concerned with "calling the election on election night," which some SB 326 supporters contend ensures voter confidence in the election system, the fact is that North Carolina's results aren't official until the canvassing and certification process (see NC General Statute Chapter 163-182: "the entire process of determining that the votes have been counted and tabulated correctly, culminating in the authentication of the official election results") is done ten days after Election Day at the county level, followed later by state board review. One could consider that this deflates the arguments about knowing an official "clear winner" the evening the polls, and voting, closes.

If the SB 326's real objective is ensuring citizen confidence in knowing who the winner is on Election evening, then the certification and canvassing needs to be revised as well. But you'll probably find significant arguments against that, and from an election administration perspective, rightly so.

Dr. Michael Bitzer is the Leonard Chair of Political Science and professor of politics and history at Catawba College, and tweets at @BowTiePolitics.