Five takeaways from the 2022 elections

Published November 17, 2022

By Chris Cooper

The 2022 election has mostly drawn to a close. I say mostly because we are still waiting on a few more ballots to be counted, provisional ballots to be sorted out, and perhaps a recount or two. Nothing is final until the state canvass on November 29 (county canvass on Nov. 18 is also a key date to keep in mind). See this Hansi Lo Wang piece for a good overview of why these details matter nationally and here for the NC-specific post-election procedures.

Soon after canvass the NC State Board of Election will release an updated voter history file that will include a row of data for everyone who cast a vote in November, 2022. At that point, we'll be able to answer questions about the patterns of who voted (what happened with youth turnout, female turnout, minority turnout, etc.).

So, I'll pause on all individual level turnout conclusions, but there are a few things that I think are safe to conclude from the data we do have available. If you have not already, I encourage you to first read this excellent wrap-up from Michael Bitzer that lays out a number of important points that I try (with varying degrees of success) to stay away from in what follows.

1. The Disappearing Swing Counties Prior to this election it appeared that counties, like other geographic units in North Carolina are increasingly Republican (red) or Democratic (blue), with fewer and fewer vacillating between the two or taking on shades of purple.

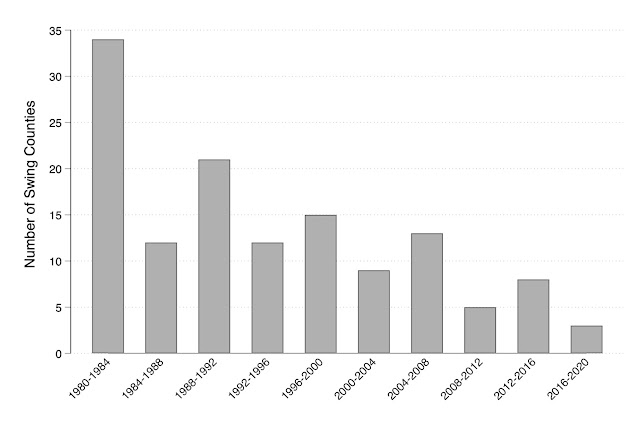

For example, the figure below shows the number of counties that switched partisan allegiances in Presidential vote choice in back to back elections (inter-election swings) from 1980-2020. Thirty four counties in North Carolina switched partisan allegiances for President from 1980 to 1984; from 2016 to 2020 that number dropped to three (New Hanover, Nash, and Scotland).

In 2022 that trend of increasing county partisan sorting continued. Just three counties gave the plurality of their support for Cal Cunningham in 2020 and Ted Budd in 2022: Anson, Nash, and Wilson. No counties supported Tillis and Beasley. Likewise, no counties supported Trump and Beasley or Biden and Budd. Clearly county-level partisanship is (to borrow a term from Michael Bitzer that he borrowed from John Sides, Chris Tausonovitch and Lynn Vavreck), calcified.

Another way to identify swing counties is to look at intra-election swing counties--counties that give the plurality of their votes to one party's candidate for one statewide office and to another party's candidate for another statewide office. For example, in 2020 Granville, Lenoir, Martin and Scotland Counties supported Democrat Roy Cooper for Governor and Republican Donald Trump for President.

In 2022 the number of intra-election swings was once again, small. Out of a hundred counties, just New Hanover and Washington Counties split their partisan allegiances for U.S. Senate and NC Supreme Court (Beasley is only up 3 votes over Budd in Washington, & Deitz and Allen are up by fewer than 100 votes so take that one with a grain of salt & check back after canvass). Pitt County also qualifies as a swing county as they supported Democrat Sam Ervin III for one State Supreme court seat and Republican Richard Deitz for the other (before you ask why, I'll confess that I have no idea).

If you put all of that together, it suggests three things: (1) most counties are clearly blue or clearly red, (2) county-level voting patterns are consistent, (3) if you want to make a list of swing counties, a good starting place would be: Anson, Nash, New Hanover, Pitt, Washington, and Wilson.

2. What about the Movers?

Most counties are clearly in one camp or the other, but that doesn't mean that they are all stable; some counties are moving more towards one party than the other. As one way to look at partisan shifts, I calculated the percent change between Ted Budd and Thom Tillis' two-party vote share.

In the graph below you'll see the five biggest movers towards the Republican Party (counties where Budd did much better than Tillis) and the five biggest movers towards the Democratic Party (Beasley did much better than Cunningham). As you'll see, Democratic gains came largely in counties that already heavily favored the Democratic Party.

3. Female Representation in the General Assembly Increased

It is no secret that Women are underrepresented in North Carolina government and politics. See the excellent work from the Status of Women in North Carolina: Political participation for background and context.

There was some (limited, but important) improvement on that front from the 2022 elections. The North Carolina House moved from 27 women to 33 with Democrats experiencing a jump from from 19 to 25. The number of female Republicans stayed constant (8 before and 8 after).

There will be 17 women in the NC Senate at the beginning of the 2023 session, an increase of one female representative overall. The Democratic Party will have three more female representatives than they do in the current session while the Republicans will have two fewer.

Colin Campbell reviewed some of these numbers, along with other demographics shifts in yesterday's NC Tribune (if you're not subscribing to the Tribune, I recommend it).

4. Continued Change to the Way We Vote

In 2020 mail voting moved from a rarely used form of voting in North Carolina to one that was used by almost one in five voters. Election day voting, by contrast, was used by fewer than 20% of all voters in 2020.

While no credible observer thought that mail voting would reach those types of numbers again, there was much more debate about exactly where mail voting would settle in and whether election day voting would return to previous levels.

The graph below shows the percent of the electorate who chose various methods of voting from 2006 to 2022 in North Carolina. The 2022 data are unofficial and incomplete and will shift slightly after canvass. In particular, the number of mail votes will increase.

Despite this caveat, it's safe to conclude that mail voting is more popular than it was in the past, but will fall far below it did in 2020. Election day will likely come in slightly up from the last midterm and election day voting will likely decline slightly from 2018

5. Maybe 2018 is the Weird One

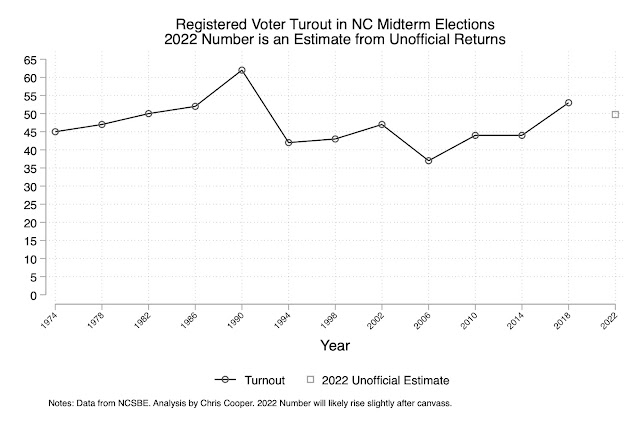

I thought voter turnout in 2022 would exceed 2018 turnout. The logic was two-fold. First, 2018 was a blue moon election; there were no statewide elections on the ballot. In contrast, 2022 featured a potentially competitive U.S. Senate race. Surely that would translate to higher turnout. Second, turnout in 2020 was the highest in over a century; I expected that some of the new voters who cast a vote in 2020 would do so again in 2022.

I was wrong.

The graph below shows registered voter turnout from 1974-2022. The 2022 results are unofficial and do not include many absentee and provisional ballots that still need to be received, which is why I denote them differently than 1974-2018. Even with that asterisk, it is extremely unlikely that 2022 will exceed 2018.

There are a couple of ways to read that finding. One is to focus on the fact that turnout was down. And that's true.

On the other hand, 2022 will likely end up with the third highest midterm turnout since 1974. From this perspective, maybe 2018 is the odd ball and 2022 turnout actually reveals something more positive about political engagement than a simple comparison to 2018 might suggest.

Wrapping Up

Christopher Cooper is the Madison Distinguished Professor of Political Science and Public Affairs at Western Carolina University. He tweets at @chriscooperwcu