Abraham Lincoln and the Declaration of Independence

Published 2:31 p.m. yesterday

By Thomas Mills

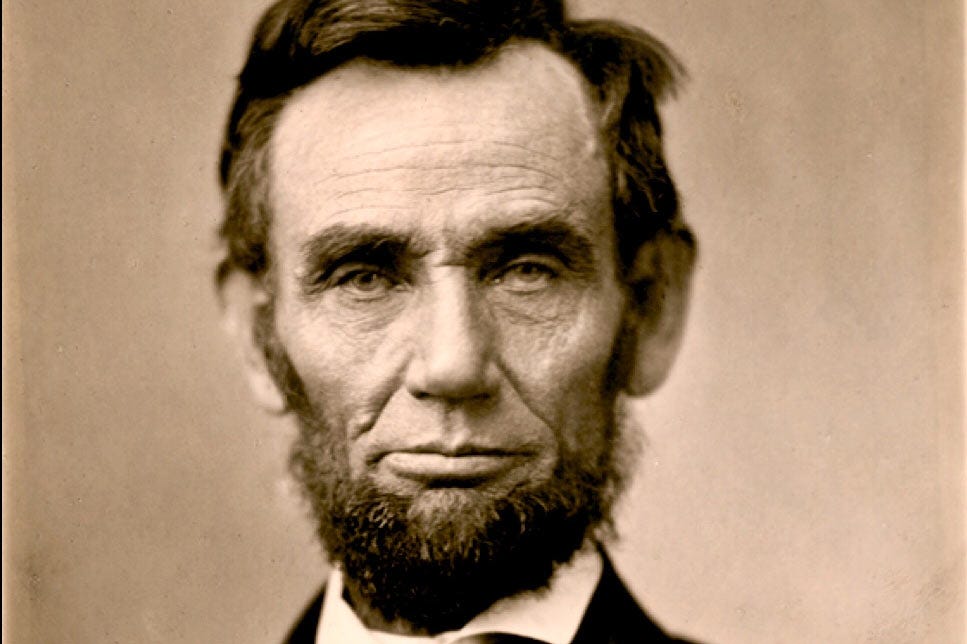

I often look for periods in history that offer insight into our current situation. Since January 6, I keep coming back to the period leading up to the Civil War and the man who guided the country through its most perilous moment. Abraham Lincoln brought a calm temperament to the White House in a turbulent time. As he faced unrest similar to what we face today, Lincoln turned to the Declaration of Independence to guide us through the storm.

In 1860, the country was undergoing a technological and communications revolution. In a sprawling and wild land, the introduction of the railroad was making the country smaller, tamer, and more interdependent. A train could deliver people and goods from Chicago to New York in just a couple of days instead of several weeks. The introduction of the telegraph instantly spread information that had once taken days, weeks, and even months to reach people. The ability to move people, goods, and information so quickly was transforming the nation.

These new forms of communication and transportation weren’t embraced equally. While the emerging industrial North saw them as opportunities, the antebellum South saw them as threats to their way of life. Trains heading North offered their enslaved workforce a means of escape. Too much information could create unrest by offering alternatives to their feudal way of life.

As the North and Upper Midwest developed into industrial powerhouses, the question of slavery further divided the nation. Many Northern cities and towns had welcomed escaped slaves as refugees, but in 1857, the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision declared enslaved people could not be citizens and had no rights. Federal Marshalls began raiding workplaces and homes in places like Boston and Cleveland, taking custody of escaped slaves and transporting them back to the South.

Across the globe, democracy was on the wane as a form of government. The French Revolution had given way to Bonapartism. The European revolutions of 1848 had largely failed to achieve their goals. At the brink of the Civil War, the United States seemed poised to end its Great Experiment, too.

As the country appeared to be breaking apart, Lincoln searched for guidance from the people who founded the country. He kept coming back to the Declaration of Independence. In And There Was Light: Abraham Lincoln and the American Struggle, historian Jon Meacham argues that Lincoln saw the Declaration as foundational, giving clarity to the righteousness of the coming war. Lincoln was defending the vision and lofty ideals of the Founding Fathers.

Lincoln thought that slavery was incompatible with the Declaration and with democracy. In Lincoln on the Verge, Ted Widmer says Lincoln believed slavery “violated every one of the rights proclaimed by the Declaration—not just life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, but the general idea that government derives its legitimacy from consent.” He believed the promise of our country was that all people are created equal and that our rights are universal.

Lincoln viewed the Declaration as an ideological document that provided us a moral compass. He saw the Constitution as secondary, a political agreement hashed out to give us rules for governing. His belief that the universal truths spelled out in the Declaration superseded the feudal political desires of the Southern states led him to take us to war.

Lincoln so believed in the concepts of the Declaration that he was willing to immerse our country into a struggle that killed more than 600,000 Americans. He stitched together the tear in our country with the lives of our people. He must have known that it would take decades to heal, even if he couldn’t know that we would still be struggling with many of the same questions today.

Lincoln embodies the promise of the Declaration. He was extraordinary, in part, because he seemed so ordinary. He had no advantage at birth, but rose to the highest echelons of power in the emerging nation.

And like the nation, he often fell short of the ideals of the Declaration. He permitted the mass execution of Dakota Indians. He suspended habeas corpus. Still, his faith in the United States was grounded in the belief that our country would be a force for good, promoting equality and justice for generations and beyond our borders, not just the America of 1860. He saw the Civil War as a fight for universal truths that bound the colonies in their quest for independence, not just the territory that made up the South.

Lincoln’s belief in the Declaration should be our guiding light as we fret about our future. The idealism of the document shows us who we should aspire to be as a nation. It tells us what to fight for and what to fight against. We celebrate the day our Founders signed the Declaration of Independence, not the day the Constitution was ratified or the day Cornwallis surrendered to Washington.

The bedrock of our country is a document that reads:

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness. That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. Prudence, indeed, will dictate that Governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and accordingly all experience hath shown that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.

Happy Independence Day.